Where are they now?

YIWEI CHAI (2017)

I started at Pymble as a Year 7 scholarship student with very little interest in STEM.

My whole life, I’d loved reading. My favourite place on campus was the Conde Library; the smell of the stacks, the rows upon rows of books, the little nooks and the heavy swing of the glass entrance doors. I liked the secret feeling of finding a promising novel on the very bottom row of a shelf, which you could only do if you sat on the carpet and tilted your head to one side to read all the spines. I spent many wet-weather lunches there, and also idle after-school hours where, instead of doing homework, I would sit with friends at one of the round tables on the ground floor and chatter about characters and stories.

If you had asked me in those years what I wanted to do after high school, science would have been the last thing on my mind. The humanities — writing and languages in particular — had my absolute loyalty. Science and maths classes, I sat through largely with indifference. That is not to say I did not have good teachers, but rather, I simply did not think of myself as ‘a STEM person’. Understanding graphs never came naturally to me. Science reading comprehension passages were an exercise in both boredom and frustration. I still remember sitting on a bench at Turramurra station one morning in Year 8, waiting for the train, and crossing out and rewriting and crossing out and rewriting my answers for our first ever ‘introduction to binomials’ homework sheet. By Year 11, I gleefully replaced chemistry with visual arts, and kept maths only because I was told it would be ‘helpful for my ATAR’. For the HSC, I took four units of English, three of Ancient Greek, Latin Continuers and Maths Advanced. (In theory, I suppose I did take Maths Extension 1, but I ended up dropping the course in a fit of panic one week before I had to sit the actual exam. The HSC is truly an interesting period of one’s life.)

Now that I look back on things, however, I wonder how much of this way of thinking, of saying ‘I am a STEM person’ or ‘I am not a STEM person’, is because of what is true, and how much is simply because of what we tell ourselves to believe? In my time at Pymble, I did actually have the opportunity to engage in many maths and science activities. There was the maths tour to the Gold Coast in Year 7, the University of Sydney’s Gifted and Talented Discovery Program in Year 9, the Great Engineering Challenge at UNSW in Year 10, annual AMO competitions, the occasional olympiad, accelerated maths and, frankly, a curriculum whose rigour I did not entirely appreciate until I began the application process for universities in the States and had to sit for US-based standardised testing.

Perhaps it is a testament to the sheer number of opportunities made available to Pymble students, academic and otherwise, that I, as a self-proclaimed ‘non-STEM person’, nevertheless managed to participate in so many STEM-related activities. Indeed, I think of the many opportunities afforded to me throughout my time at Pymble that I otherwise would not have been able to enjoy. That I was able to take a wide range of subjects, and dabble in extracurriculars from debating to fencing to sailing to drawing, is something I feel very grateful for. It has opened my mind to possibility, and encouraged me to try new things that otherwise might seem fanciful or out of reach.

Left: Great Engineering Challenge at UNSW in Year 10. Right: Language Arts Tour to the US in Year 12.

After graduating from Pymble, I ended up attending the University of Pennsylvania, a mid-sized research university in the city of Philadelphia. It was the only US university I was accepted to, and I was drawn there in large part because of the Kelly Writers House — a small Victorian cottage tucked away on the west side of campus that is host to a vibrant undergraduate literary community. Another aspect I appreciated was that students did not have to decide on a major until the end of the second year. Instead, during my first two years, I was encouraged (and in fact required) to take a breadth of classes in a wide range of fields. I had to fulfil coursework in the social sciences, foreign language, the arts and humanities — but also in the natural sciences and quantitative reasoning. It was to satisfy one of these requirements that, in the spring of my first year, I decided to take an introductory astronomy class on the solar system and extrasolar planets.

How to describe the fascination around the topic of extrasolar planets, or ‘exoplanets’? There is something remarkable about the fact that we are able to detect — and even probe the characteristics of — other worlds orbiting stars beyond our own Sun. The existence of these exoplanets naturally raises questions: how are they different to the planets we know? Why? Is our solar system special? Is our Earth unique? And perhaps the most fundamental question of all: are we alone?

After the first few lectures, I was captivated. The instructor for the class was Professor James Aguirre, a dry-humoured man who had a knack for explaining high-level science concepts to a lecture hall full of students with an aversion to equations. I found myself going to office hours every week. I started with questions about the homework assignments, and progressed to asking about theories, current observations. How did scientists actually know about the concepts we were learning in class? What tools did they use to make discoveries and expand our knowledge of the universe? I had never been so curious about what lay beyond the course material before. Perhaps because of this, at the end of the semester, Professor Aguirre asked if I was interested in doing a summer research internship. I was, at the time, the furthest thing from a physics major. I had no coding experience, had never taken a formal physics class, and had not thought about calculus since putting down my pencil at the end of my HSC maths exam. But in the end, despite my reservations, I was still curious enough about astronomy to say yes.

Outside of teaching classes, Professor Aguirre’s work largely involved studying the very early universe to understand how the first galaxies formed. One of the ways he did this was by designing and building balloon-borne telescopes that would be launched high into the Earth’s atmosphere above Antarctica. Once launched, the balloon would be at the whim of the elements, so in order to understand where the telescope was looking, it was necessary to have an array of sensors on board to transmit GPS, orientation, travel speed and other data in real time. That summer, I learned how to build a simple digital thermometer on a circuit board, and write code that would concurrently record the temperature data it took into a database. The idea was that this project would then be expanded to the real sensors, so that their behaviour could be tested in both laboratory and in-flight conditions.

The work was challenging, but rewarding. Professor Aguirre was a patient mentor, and his graduate students were generous with their advice and encouragement. I started to wonder if, perhaps, I was capable of doing astronomy research. The next semester, I tentatively enrolled in the first set of required courses for the physics major. I was worried that I would be a year behind all my peers — but to my surprise, I discovered that what I had learned at Pymble meant that I was well positioned to understand my calculus-based mechanics course and could directly enrol in multivariable calculus. I managed to do well enough in this first set of classes that I felt I could sign up for the next set. By the time my second year at uni came to an end, I declared a physics major with a concentration in astrophysics.

Left: Fiction workshop at the Kelly Writers House. Right: Hiking with fellow summer research interns at the UC Berkeley SETI Research Center.

Now, I am halfway through my fourth year of a PhD program in astronomy and astrophysics at Johns Hopkins University. In my research, I’ve returned to those fundamental questions that so piqued my curiosity in that first astronomy class. What can we learn about the nature of planets and planetary systems? How do they form and evolve over time? To investigate these questions, I study exoplanet atmospheres with two of NASA’s flagship space telescopes: the James Webb Space Telescope, and the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (named for NASA’s incredible first Chief of Astronomy; she is worth looking up). It’s not always easy, but it is wonderful and interesting work; I feel very lucky that, every day, my job is essentially to learn new things about our universe.

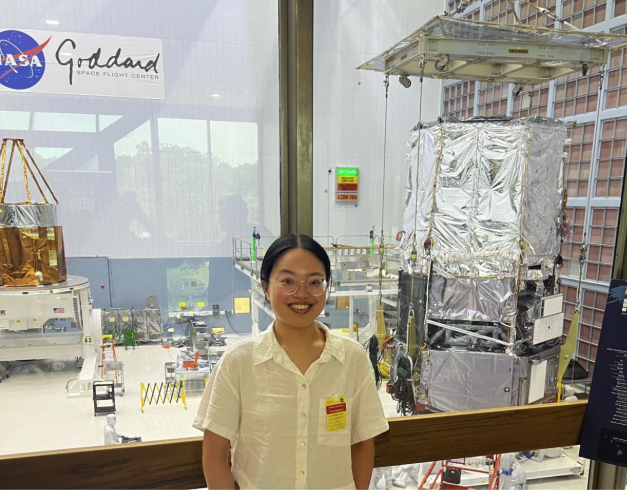

Left: At NASA Goddard. Behind me is the actual Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope that will be launched earliest late next year! Right: Presenting on Roman exoplanet science at the 245th American Astronomical Society meeting.

A PhD program in the States is combined with a research Master’s, so it takes a long time, often around five or six years. Throughout this time, I have been fortunate enough to work with two truly wonderful advisors, who have supported and encouraged my growth as a researcher. I have had the opportunity to travel all over the States (and overseas) to attend research conferences. And I have met so many incredibly clever and interesting people who are very passionate about the work that they do.

It’s not something you think about as a teenager, bemoaning the purpose of writing yet another PETAL paragraph or having to show your work down the page in maths class, but the longer I have been in academia, the more I find that Pymble has provided me with a strong foundation of fundamental skills crucial to being a good astronomer. There is a surprising amount of writing in research: observing proposals for telescope time, grant proposals for research funding, abstract submissions to present at conferences, and of course the lifeblood of an academic career, papers. The years of debating have meant I’m comfortable with giving talks and thinking on my feet. And perhaps the most important lesson that I learned at Pymble, that there is a world of possibilities out there if we are only brave enough to say yes, has driven me to be unafraid of pursuing new projects and trying new things in my research.

Outside of research, I still love reading novels and writing of the non-academic sort, and have picked up rock climbing and figure skating. I now live in Washington DC with two rambunctious cats, and recently got engaged. As for what comes next, I hope to finish my thesis in the next year or two. After that, perhaps I will find a postdoctoral research position and continue doing exoplanet science, or perhaps I will end up pivoting to something else entirely. But I know that, regardless of where I end up, the strong foundation of skills — and the drive to explore — instilled in me by my time at Pymble will continue to serve me well.